Authority at Work and Tyre Nichols' Murder

Last week a federal court acquitted officers of violating Nichols' civil rights in the process of causing his death

(No. 52, a ±08 minute read)

The last thing the world needs is another think piece focused on Tyre Nichols — but his murder haunts us — and will well after the state trial of the responsible officers on second degree murder charges, as yet unscheduled, is complete. Unfortunately, his unconscionable death distills Nichols’ life into the larger substance of our national symbology where he dwells with too many Americans who have been cut down by agents of the state, acting under the mantle of state authority. And his killing, and those of others like him, is the product of the same systems of power that have brought us the climate crisis, something not often discussed.

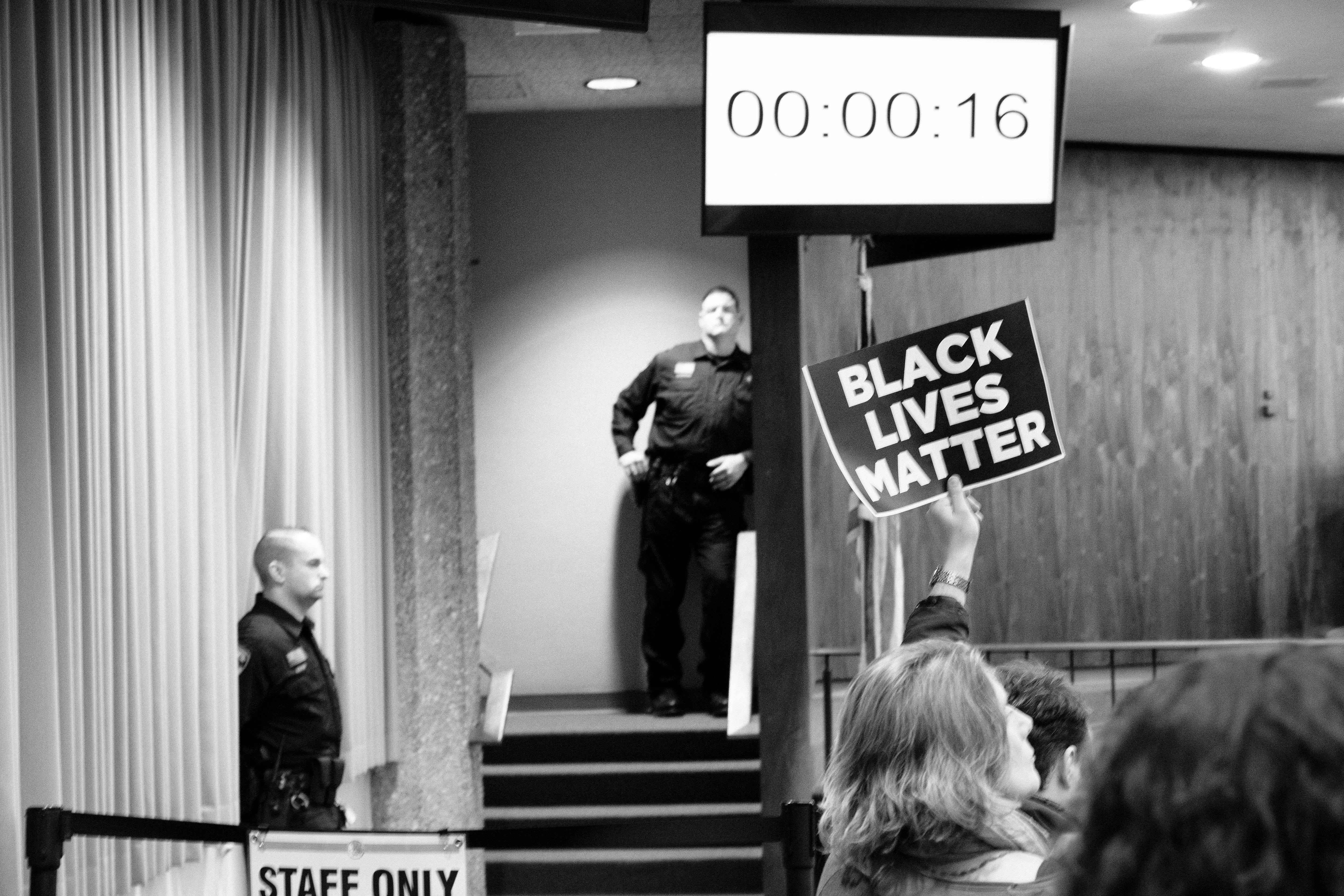

I have a quote inked along the mouth of the main compartment of my old camera bag: “We have seen authority at work, and its work condemns it entirely.” I inscribed this quote, declared by the nineteenth century philosopher, poet, abolitionist, and unrepentant anarchist Joseph Déjacque (b. 1821, d. 1864), to remind me, while working to bear witness to our world coming apart at the seams while I follow the global warming beat, to be meticulously skeptical of what I am shown and told by those representing power.

Déjacque’s quote came to be written in my camera bag by way of Guy Debord’s essential essay ‘A Sick Planet.’ In his essay the quote resides in this foreboding passage:

The terrible choices of the near future, by contrast, amount to but one alternative: total democracy or total bureaucracy. Those with misgivings about total democracy should try to test its possibility for themselves by giving it a chance to prove itself in action; otherwise they might as well pick themselves a tombstone, for, as Joseph Déjacque put it, “We have seen authority at work, and its work condemns it entirely.” [Italics Debord’s]

Debord is speaking here of the calamity of ecological collapse at the hands of the economic and social systems manufacturing this collapse while also fomenting profound individual alienation — these agents of chaos’ survival, and thriving, is predicated on exploitive depredations which cause systemic failures of ecosystems and social systems alike. I point to our present oil, tech, and social media industries in order to forestall the decrying of this as an extreme assessment.1

In his essay Debord continues, “The slogan ‘Revolution or Death!’ is no longer the lyrical expression of conscious revolt: rather it is the last word of the scientific thought of our century.” [Again, italics Debord’s] Debord wrote this in 1971, his words have only become more excruciatingly urgent in the twenty-first century.

Today Debord’s words have become not only more urgent but more truthful, and appear more broadly applicable than even they were in 1971. The circumstances of Tyre Nichols’ death describe, with chilling precision, the systemic exploitation of the powerless by established power structures seeking endless commodity production which Debord decried in an ecological context in ‘A Sick Planet.’ Predatory policing in America is essentially indiscernible from predatory environmental exploitation when reduced to a purely conceptual quintessence. There is absolutely a commodity in this social system —people like Nichols.

In either case of environmental or social exploitation both represent, and are the manifestations, of the will to dominate in the creation or protection of profit. And it is critical to note that we are all, as dwellers under this paradigm, caught up in the mechanism of our own subjection — even those cops who killed Nichols. But Nichols, as does any ecosystem, exists as more than a conceptual quintessence, he was a person, beloved, with a role to play in the workings of the world — no matter how small it might seem, or have been. This will always be his, and all of our, essence, our influence in the world.

Nichols found solace and survival in an America that seemed indifferent, or even hostile, to his presence in it by skating it. In his case it’s not hard to develop a scenario where the necessity of such a relationship came to pass: the childhood death of a parent; his atypical physical aspect due to his uncommon thinness, a consequence of Crohn’s disease; his blackness, in a society that has shown an easy willingness since its inception to extinguish blackness for either power or profit, or both; the lifeline of his bonding with other “misfit” skater kids in Sacramento, providing him compatriots and a tribe existing outside of society more generally; his attempting to sustain himself in a crushing and stratified California economy pushing him to Nashville; the difficult responsibilities of being a young father.

Skateboarding has, since I was a child in the 1970s and ‘80s, given oddball, outsider kids a focus that denies the faddishness the pastime has occasionally known. The need to stay balanced while skating a pool or doing a trick in the streets demands a focus that blinds a skater to all but that moment alone. The consequences of allowing concentration to slip are immediate and bruising. In a world in which so many signs point to decline and deterioration, and individual lives are as challenging as they regularly are, the absolute focus of executing a trick on a skateboard is undeniable, though momentary balm. If Nichols’ story is anything like mine, skateboarding delivered him this balm — but for his own unique, individual reasons.

Skateboarding, for all of its being brought into the capitalist and social fold and out of its delinquent past, is necessarily apart from society — but that society is one we all must return to; whatever our escapes might be. We adjourn our recess to face the stories our society weaves; the stories that we allow it to tell. Nichols returned from his place of respite to confront two such stories. These two stories compete for oxygen with second of them comprising a falsity and backed by the power of the state; the will of the big. But the primary story is simple and plainly true; a young black man was stopped, pretextually, by police offers — agents of the state — who over the course of their interaction with Nichols, assembled themselves into a gang and indefensibly beat him to death.

It is a story that by its clarity necessarily reduces itself to a power dynamic — we in uniform are in charge and you mean nothing to us. It is a story probably as old as humankind and repeated endlessly around the world. (Yevgeny Nuzhin became a victim of this recurrent tale, by sledgehammer, at the hands of Putin and the Wagner Group, after his defection as a Russian prisoner-conscript in the Ukrainian war, just as all Ukrainians have come to understand the simple logic of the violence power might unleash. Palestinian and Lebanese citizens are learning this lesson today at Israel and its enablers’ hands. I could continue, and remain firmly in this very month around the world by way of accounting this age-old human dynamic.)

This story of power’s projection and consequences is not only the story of war, it is also the story of oil companies (or logging concerns, or…) world-wide in the face of accepted and irrefutable causal evidence of global warming, as they continue to work to mint a buck until the bitter end. In the context of power dynamics Nichols’ death was a lynching — the destruction of life to assert the power of a system to exploit that which feeds the system.

This story is simplicity itself, it repeats all around us, consuming human and non-human victims. A polity’s ability to face the consequences of this story, and address them — honestly and constructively — is the true test of its powers of self-realization and self-preservation.

The second story Nichols’ death unfortunately illustrates is a zombie fable, backed by the state and ever refusing to die. It’s also simple, and it goes, “Every time you leave the precinct house your life is in mortal danger, placed there by the virulent brutality inherent in those whom you police. Every citizen you engage with, stop, or otherwise face on the streets of your shift can and will, if given the chance, end your time in this paradise we have made on earth.” This stance creates an embattled method of policing which statistics don’t support.

The most dangerous thing a cop can do is a traffic stop? Of course — there are more cops killed or injured stopping vehicles than any other task they complete. But it is the most often undertaken task, bar none, police officers do. Controlled for volume of action it is not the most dangerous thing cops do at all. In fact, the vast majority of police officers never draw their guns on duty and never get in a substantial physical altercation on their beats — in the whole of their careers.

So how does this story shamble on? Being a cop isn’t even among the top five most deadly occupations in the U.S. (in order: logging, commercial fishing and processing, pilots and flight engineers, roofers, garbage and recycling collectors). Policing is fourteenth on the list. It is just before power line workers and right after construction laborers. The story dodders on because power keeps it alive to entrench its power, or profit. Police unions, firearms and other policing equipment manufacturers, the racketeers operating prison and jail systems, those whose capital investments alienate us from the earth and its natural systems and who rely on the police to protect their investments, the politically powerful; all of these and more contribute to retelling this zombie fable.

Fear sells power — where are today’s internet-popular construction laborer champions? Where are the “dirty brown line” stickers signaling allegiance with the protection of society from body-wracking toil on a dusty job site populated by immigrant Latino laborers?

Exactly.

The complicity in telling this blue line enforcement fable, and muddling reality’s clarity, extends even to the Fifth Estate. Take this New York Times headline: ‘Tyre Nichols Beating Opens a Complex Conversation on Race and Policing,’ from January 28, 2023. It does no such thing. Nichols’ murder defines power absorbing the identity and agency of its representatives. It clarifies Déjacque’s quote. “We have seen authority at work, and its work condemns it entirely.”

Nichols’ having been beaten to death, even by black men in uniform, is merely another story of power, subjugation, and exploitation; not a new opportunity for dialogue. Such declarative headlines offer us nothing about policing, or race, that has not already been answered by public health inquiries into improving outcomes of that that same policing — or being black in the U.S. — except a denial of understanding what we have long known.

Nichols’ beating, contrary to the Times’ declaration, offers no complexity of understanding of race in our nation — we have long known that enough power and social status generally trumps race in the American poker hand. And what of all those police-beaten who don’t die, don’t make the news, drive protests? Does their absence from the public eye mean they don’t exist? Aren’t fodder for exploitive justice and carceral systems’ profits? Aren’t overwhelmingly young men of color?

The dialogue Nichols’ murder opens, or should open — just as the fires in the American West, flooding in its plains states, hurricanes on its eastern and southern coasts should also open it — is a difficult conversation that is preliminary to the re-configuring of our most basic societal structures to be sustaining, and not exploitive. Do we have courage enough to face our comforts and fears and engage in this conversation, honestly, and act fruitfully on it? Are the powerful willing to cede any of their power? Can we make another way on earth than that which is destroying it and killing us?

These are the questions of our time and this is the complexity Nichols’ death should open for us. His murder provides an opportunity to see ourselves for what we are, broadly, and improve what we find. But undertaking this we can be damn-well sure that power will fight to the death to protect its station when we, finally, consider to answer these questions openly and thoroughly, with an intent to change.

Tyre, may you evermore skate and create, wherever you are; and may you teach us that to skate and destroy was never the answer, no matter what Thrasher Magazine might have told us, and as marginalized as any of us might have felt — with validity or not. I’m clapping the tail of my board on the coping for you even as the court system let you down last week.

I can’t recommend enough this essay in the current issue of Harper’s Magazine. It admirably tackles the poisoned relationship between tech monopolies and rule of law, and political representation: https://harpers.org/archive/2024/10/the-antitrust-revolution-big-tech-barry-c-lynn/